You can easily imagine the product development meeting at AKG back in nineteensixtysomething…

Or something like that. It is certainly true that AKG made some great microphones (too many to list) and a lot of nasty ones (also too many to list). The AKG BX10 and BX20 spring reverbs have become studio classics. And so if any company was well positioned to make a microphone with a built in reverb, it had to be AKG. The result is the AGK BX11, which is a battery powered dynamic microphone with a built in single spring reverb and a battery powered circuit which uses five germanium transistors to amplify the signal and drive the reverb spring.

|

| AKG DX11 echo microphone |

There are some major shortcomings to this design. It is impossible to use this as a hand held microphone because the spring just rattles around. The microphone capsule is not great quality, battery life is short and the germanium transistor circuit is noisy. And although the microphone element is certainly not of hi-fi quality, and the spring is ‘boingy’ rather than lush, none of that matters because it is quirky and fun and offers something unique.

|

| AKG DX11 capsule and circuit board |

The owner of this one had enquired about converting the mic to run on phantom power, but that was not trivial because the circuit has a positive ground, and I also had doubts over whether we could supply sufficient current with phantom. The output of the microphone of the DX11 is unbalanced 15K ohms or unbalanced 200 ohms.

|

| AKG DX11 spring reverb |

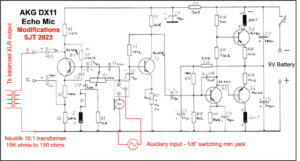

I added a small Neutrik 10:1 transformer to drop the unbalanced 15K output down to a balanced 150 ohms*, which makes it a bit more compatible with mic preamps and mixers, and wired to a normal balanced XLR output. The transformer fitted in neatly in the cavity behind the capsule. (*You could use a 1;1 transformer from the 200 ohm output).

|

| DX11 circuit hacks – Click on the image to see a bigger version. |

After a bit of initial testing, I came to the conclusion that reverb is better than the microphone, and so, after a discussion with the owner, we decided to fit a line input to the reverb circuit. The microphone capsule itself has a measured output of 250 ohms, so it was easy to hack into the circuit at that point, via a switched mini-jack socket. Now one can run other things into the reverb, such as a better dynamic or ribbon mic, a quiet line input or a guitar via a DI box.

Here is a picture of Adam from Extinct Audio test-driving the DX11 reverb (on the bench) with a Jazzmaster guitar…

I hope to share some sound clips soon.

Further reading