|

| Small Toshiba Ribbon mic |

Toshiba are better known these days as a giant manufacturer of consumer electronics goods, so it is perhaps surprising to find a ribbon microphone with their name on. In fact back in the 1960s Toshiba made some pretty decent models, some of which were good copies of RCA mics.

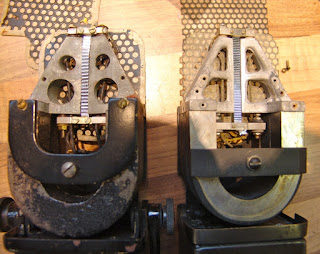

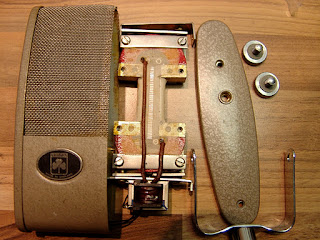

February’s microphone of the month is this little ribbon mic, which lacks a model number, but has been referred to as an RCA74b clone. However, although from the outside it resembles a smaller 74b, inside it is very different.

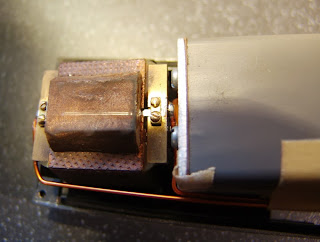

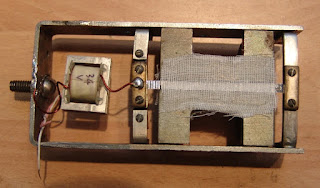

Beneath the outer grills lies a perforated metal baffle backed by a finer mesh screen, which protects the full length of the ribbon against air blasts and pops. The top and bottom of the shield have a tendency to go ‘ping’ – I could actually hear this ringing when speaking into the mic, so a little bit of sticky foam was used to damp this.

|

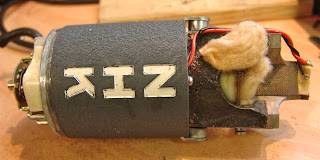

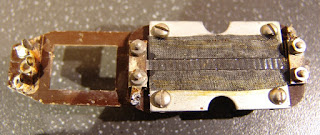

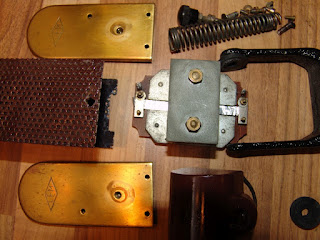

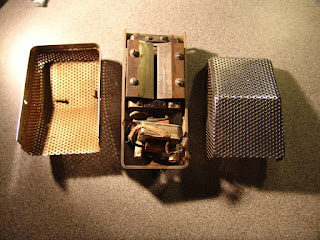

| Rear of the Toshiba showing transformer and magnets |

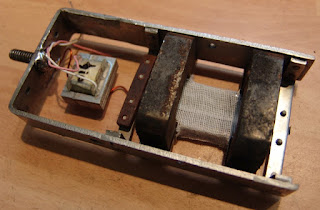

From the rear, we can see that the field is suppled by a pair of strong horseshoe magnets glued to the pole pieces, which give a measured field of about 3000 Gauss between the poles. The transformer is a twin core ‘humbucking’ type, in this case wound for high impedance.

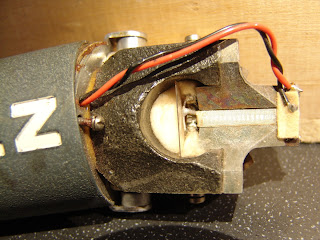

Once the inner screen is removed, two features stand out as unusual. Firstly, there are no ribbon clamps! The ribbon is simply glued to the supports, and then soldered to the terminals. The arrangement works well enough, but you only get one go at fixing the ribbon.

|

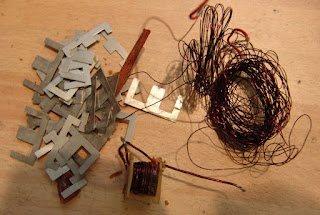

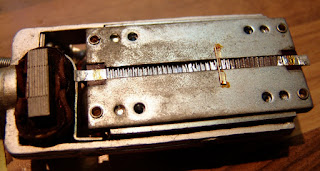

| Toshiba ribbon |

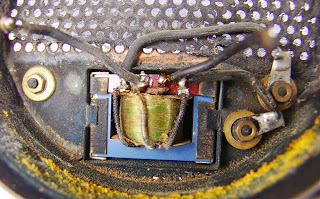

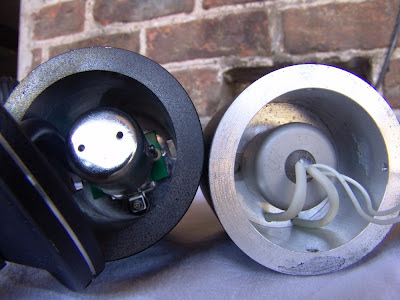

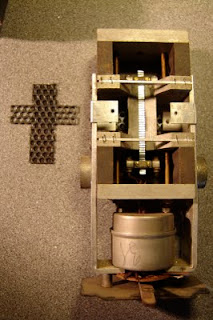

The second interesting thing is the small cross bar that bridges the pole pieces. This is actually glued to both the pole pieces and the ribbon itself, dividing the 3.6 mm wide, 60 mm long ribbon into two sections in a 3:2 ratio. I can imagine two purposes for this – to stop the long thin ribbon from travelling to far, and to minimise overtones from harmonic motion.

I have also seen this ‘node’ on another Toshiba ribbon model, so it does seem like a little trick of theirs. The nearest thing I have seen in other microphones is in the Cadenza mics, where the ribbon is glued to a support half way along.

|

| Microphone cleaning |

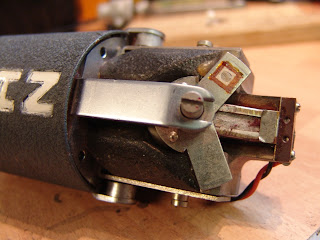

This mic was rather dirty inside. Lots of little bits of iron were interfering with the ribbons movement, making it sound like it was scraping against the sides – which it was! These were easily cleaned with some sticky tape, but the ribbon had to be sacrificed first.

|

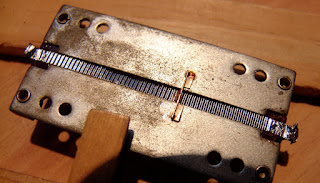

| New ribbon in the Toshiba mic |

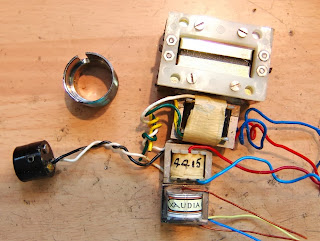

A new ribbon was fitted – soldering 1.8 μm aluminium foil is a bit tricky, but I got the hang of it after a couple of tries. And gluing the cross bar to the ribbon also requires a steady hand!

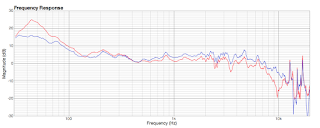

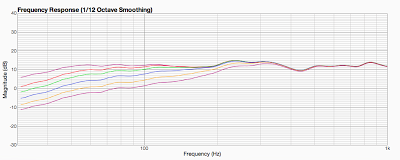

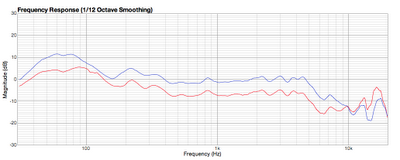

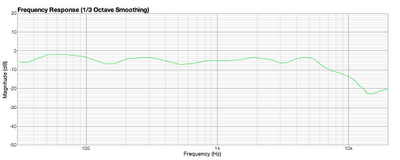

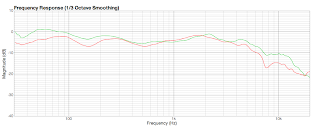

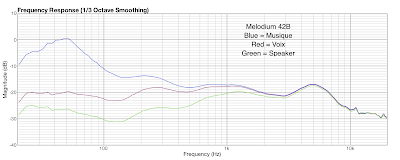

Once re-ribboned and reassembled (and fitted with a low impedance transformer), the microphone sounds nice, with a relatively flat response up to around 6KHz, where it begins to roll away.

|

| Frequency plot for Toshiba ribbon mic at 35 cm. |