Last week’s technical article talked about different methods of connecting a condenser capsule to the grid of a tube amplifier, in order to build a tube mic. In this part we consider how to connect a capsule with two diaphragms in order to get a multi-pattern mic.

First let’s examine the different pickup patterns available. There are three extremes: Omni, where the microphone hears sounds equally in all directions. Cardioid (heart shaped*), where sensitivity is greatest in the direction in which the microphone is pointing, falling off to a null point behind. And Figure-of-Eight, with equal (but opposite) pickup in front and behind, and null pickup to the sides. To complicate things further, the pickup pattern may depend upon the frequency, and some mics will have good directionality at higher frequencies, but become less directional as the frequency drops.

But what if we want a microphone with selectable pattern? This can be achieved by arranging a pair of cardioid capsules back-to-back, and combining there signals in different ways. We’ll call these capsules front and back, although of course they could be pointing in any direction. If we require a cardioid signal, we just take the front capsule and for omnidirectional pickup, we mix both signals equally. If we want figure of eight, we subtract the output of the rear from the front: where the signals overlap at the sides of the microphone, they cancel each other out producing null points. Other patterns such as hyper-cardioid and super-cardioid may be considered as in-between positions of these extremes.

So, what is the best way to achieve this practically in our hypothetical tube microphone? Two of the earliest commercial mics with more than one pattern were the Neumann U47, which offered cardioid and omni, and the U48, with cardioid & fig. 8. Let’s look at the U47, as this is probably the simplest way to combine the two capsules.

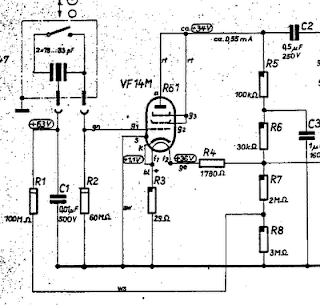

In the U47 the front diaphragm is grounded through a 100 Meg grid resistor, and the backplate of the microphone’s dual diaphragm is polarised with about 60V, providing the potential difference required. The rear diaphragm is connected to a switch. When the switch is open, the rear capsule is left floating and only the front cardioid diaphragm is active. When the switch is closed, the rear capsule adds its contribution to the front, making an omnidirectional microphone.

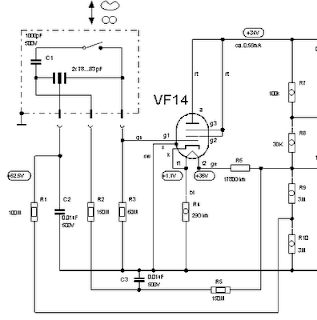

What about the U48? We have seen above that if we require figure of 8 instead of omnidirectional, we must subtract, rather than add, the sounds from the rear. To do this we must invert the polarity of the rear diaphragm by reversing its relative charge. So, rather than grounding the rear diaphragm, we must raise the potential by 60V** above the backplate, and 120V above the front capsule! This is easily achieved by using the HT supply to the anode of the tube, but creates another problem. We can’t simply connect the two diaphragms because they are now at different potentials, and so a blocking capacitor must be used. The circuit looks like this:

Finally, to make the microphone have variable pattern, we simply need to make a supply that is adjustable from 0V to 120V, and apply that to the backplate. Alternatively, the signal may be taken from the backplate, through a capacitor to the tube grid. The Neumann-Gefell UM57 does it exactly this way, with the pattern selector in the power supply.

*Really more kidney shaped, and in some languages this is the word used.

** In fact the U48 operates around 50V / 100V.