Sony made a series of excellent large diaphragm condenser microphones, some of which have become studio classics. The earliest production model was the C37A, a tube microphone which may or may not have been used by Frank Sinatra – he has certainly been pictured with one – and it was definitely used to record the voices of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. It has become sufficiently iconic for at least two clones to appear, made by Mojave and Tonelux.

|

| On test – Sony C37p, C38b, C48 and C450 |

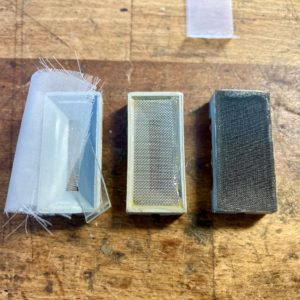

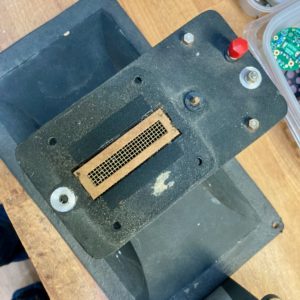

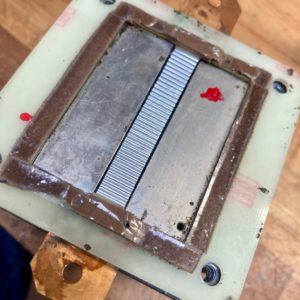

The C37P is the FET version of the C37, and is claimed to be one of the earliest production transistorised condenser microphones, although that honour is generally given to the Syncron AU7a. The C37p was followed by the C37Fet, and the C38 models. All of these microphones feature an unusual capsule design with an internal vent, which could be moved with a screwdriver from the rear of the microphone, changing the pattern from cardioid to omnidirectional. A very similar capsule is now made by Josephson Engineering, which is used in some of their own models and also rumoured to be supplied to other brands.

|

| Sony C37 capsule – front |

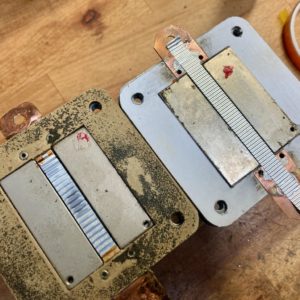

I am a big fan of the C38p and for the past 20 years have almost always used one for recording on my own guitar amplifier, often alongside a Shure 57 or whatever else is free after setting up for the rest of the band. The Achilles’ heel of this design is that the mechanism can become difficult to turn, and many the C37s and C38s are stuck in the cardioid position. For many users that is not a problem.

|

| Sony C37 capsule – rear view |

The later C48 and C800 models use a different dual sided capsule with centre terminals, which looks similar to those used widely by Neumann (and almost everyone else.) The C48 is a versatile microphone with three available patterns, bass cut and pad switches.

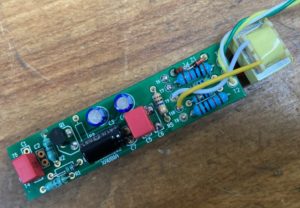

Both the C38 and C48 models can run on 9V batteries and use a DC converter inside the microphone to generate the polarisation voltage for the capsule. These converters are tricky to repair when they fail.

Sam Inglis & I recently had an opportunity to compare a few Sony condenser microphones to see how they had evolved over time. On the day of testing we had access to a pair of C37p, one C38b, a C48 and a C450. In addition we looked at a Josephson C705 for comparison.

By comparing the microphones we hope to discover how these Sony LDC mics compare and are the new ones better than the old ones (or vice versa)? Does the capsule hold the key to the Sony sound, if there is indeed such a thing? And are the new capsules from Josephson good copies of the old Sony C37/C38 capsules?

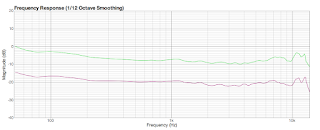

As usual, the frequency sweeps are good for comparison purposes but are run in a small booth and should not be considered absolute measurements. The reference microphone is omnidirectional, which can cause a few inaccuracies when testing cardioid transducers. The dip around 12K is an artefact. Measurements were made at 30 cm distance from a concentric speaker. Measurements were made with a swept sine measurement and recorded using Fuzzmeasure Pro.

1. Comparison of C37p, C38b and C48

|

| Comparison of C37p (lowest), C38(middle) and C48 (top) |

As one would expect, the major change between models is the increasing output level (and signal to noise). The C37p is a very early transistorised microphone and transistor technology changed rapidly in those early years. It has a nice sounding bass proximity boost, and the mic is equipped with four EQ settings marked M, M1, V1 and V2 to compensate. (M is the unfiltered output). The two C37s that we tested were very close, which is reassuring.

I own a C38b which I use it for my own recordings, and my perception is of a warm sounding microphone, without a harsh or hyped top end. I was surprised to see that it has a bit more of a top end lift than its predecessor. It carries the M, M1, V1 and V2 settings through from the C37 and also adds a high cut switch. The M1 position acts as a high pass filter whereas the ‘V’ or vocal positions are more like a long shallow shelf.

|

| C38b filter – M (red), M1 (blue) and V1 (green)

|

And the C48 is louder again. This is a more conventional multi-pattern microphone with electronic switching between cardioid, omni and figure-8. It also has bass cut and pad switches which are accessible via a sprung panel on the rear of the microphone.

In my experience the C48 is a top quality recording tool and makes a good alternative to a U87 – I know a few engineers who prefer it to the Neumann. Barkley McKay at Valleywood Studios said “one of the reasons I like the 48 is it’s gentle roll off before 16k – it’s a little like an enhanced ribbon.“

2. C48 vs C450

|

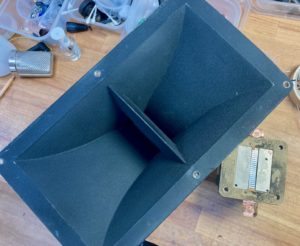

| Sony C450 capsule, front. |

The C450 is a less well known model which looks a lot like the C48 but with some cheesy 1980s stickers applied. However, the C450 has a smaller capsule, around 24mm diameter, and runs on a single 1.5V battery. We have not discussed or measured the C500 here because I don’t have access to one, but I have a hunch that this is a similar size to the capsule in that model. Can anyone confirm that or share a picture of their C500?

|

| Sony C450 capsule – rear |

The C450 has an average output level around 11 dB lower than the C48, but is significantly brighter at the top end. It is equipped with high pass filter and -10dB pad switches, although you won’t need the pad very often! The noise level is also a bit disappointing. It probably has a role on the right sound source but I haven’t found it yet.

|

| Frequency sweeps of C48 (top) and C450 (bottom) |

3. Does the Josephson C705 sound like a better C37?

|

| Josephson C705 in the testing booth at Xaudia |

The Josephson C705 is an excellent microphone with a reassuringly solid feel, and does indeed sound much like a good C37p, albeit 12 dB louder and with an even better improvement in signal to noise. It is a transformerless circuit and is cardioid only (like a lot of C37 and C38 once the capsule becomes stuck!). It lacks the high pass filter options of the Sony microphones. The C705 it is not trying to be a clone or tribute in any kind of cosmetic sense. I admire Josephson because they do their own thing and try to make the best products they can. In this case they have done some clever things with the grill and acoustic environment around the capsule, moving the vertical support struts further back out of the way of the cardioid capsule. At around £2500 this is not a cheap option, but is a professional recording tool which will get you close to the Sony C37 sound.

|

| Sony C37p (purple) and Josephson C705 (green) |

One final thought – Whilst doing some background reading for this post, I found that the older Sony mics were not highly regarded on internet forums back in the early 2000s, compared to Neumann and AKG. Here is a certain Mr K,.H.’s informed opinion..

“I never liked the C37A all that much, and would put it into the category “Post War Japan makes good” (as in their tiny late 1950s sports cars patterned after Fiats.) The C37A always struck me as a poor cousin of a ….?? Neumann mic: pretty poor craftsmanship, akin to what the Russians did in the 1970s; not much personality, pretty bad tube choice, cathode follower circuit with its associated gain and dynamic problems, etc… …and then Sony went downhill from there with its FET mics… so I think.”

I disagree. And the first thing I will do when I die and go to heaven or hell or Valhalla will be to march up to Frank Sinatra and ask him if he really did use a C37a!