Microphone ribbons are generally made from very thin metal foil, and aluminium is the ideal material as it is very light but also very conductive. The output of the microphone is inversely proportional to mass, and so a thicker, heavier ribbon will give a lower output, and a thin light ribbon will be more sensitive. Many manufacturers use something typically around 0.0001 inch or 2 microns in thickness. The ribbon is also typically corrugated either along the full length to prevent lateral motion, or at the ends to give a ‘piston’ style of ribbon. Well, that is how it should be.

However, ultra-thin aluminium is hard to get hold of, and the non-specialist may be tempted to make repairs using materials that are more readily available. Here are some things I have found inside microphones masquerading as ribbons – needless to say they were all replaced with good quality aluminium foil of an appropriate thickness!

1. Cigarette Paper.

This microphone actually worked, to an extent! It at least made a sound. The ribbon was made from an old fag packet.

Cigarette packs used to come lined with paper-backed foil – I’ve never been a smoker so I don’t really know why, but I imagine for freshness or something. The foil is thin and already textured – it just needs to be separated from the paper. Actually this last part seems to be optional, and sometimes bits of paper are still attached, making the ribbon heavy and noisy.

1.b I’ve heard that chewing gum wrappers were also used for redneck ribbons, if you want a minty fresh microphone.

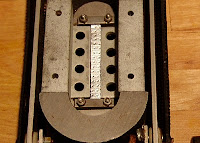

1.c Here’s a lovely example of cigarette paper being used for a ribbon in an old GEC microphone.

2. Kitchen Foil

Kitchen foil is easy to handle, yet much too thick to make a decent ribbon. But that doesn’t stop people trying. This is a common ebay trick… the ribbon looks in good condition, but when the mic arrives the output is low and sounds crunchy.

3. Sweet Wrappers

Plastic coated foil or metallised plastic, like that found in sweet wrappers is an interesting innovation, but is generally too heavy and has too high a resistance to make a decent ribbon. Also the plastic doesn’t conduct. This microphone gave almost no signal, and it isn’t hard to see why.