Here is the manual for the B&O BM5 stereo microphone, in English.

The Xaudia Blog

M320 and M360: Beyerdynamic’s ugly ducklings

We have TWO microphones-of-the-month for May. Both are cardioid ribbon microphones from Beyerdynamic. We see a lot of M260 models, but the M320 and M360 are bigger, uglier and much less common too.

|

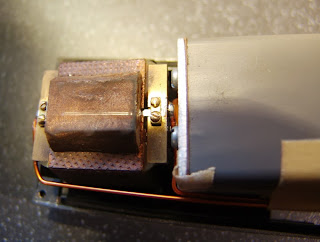

| Beyer M320. Do not stick it in your kick drum! |

The M320 makes good use of plastic for the body, and has all the style of a brick! A Beyer catalogue* from 1965 called it a “heavy-duty dynamic type for show business use”, and the switch allows the use to select ‘music’ or ‘speech’ settings, the latter giving a bass attenuation of 12dB at 50Hz. Because of its appearance and a vague resemblance to the AKG D12, it is tempting to thing that this is designed for inside a bass drum. It is not.

The M320 has the same motor that is found in the M260, but is connected to a large rectangular chamber below the mic via a tube. I have not been brave / stupid enough to cut open the chamber to see what is going on inside, but one assumes a series of interconnected tubes forming an acoustic labyrinth.

|

| Beyer M320 inside |

Although the M320 is called ‘heavy duty’, the M360 is much more sturdy, with a metal housing and grill. The catalog calls it a “dynamic unidirectional studio microphone with ultra-modern styling“. Again, it is as elegant as a 1980s Volvo, but at least form follows function in these mics!

|

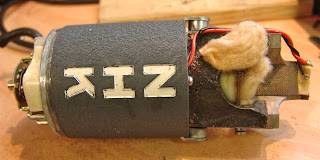

| Beyer M360. Ultra-modern? |

|

| … or just ugly? |

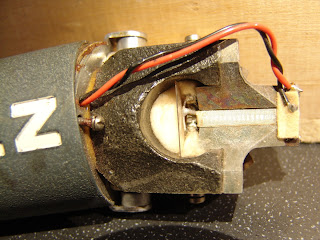

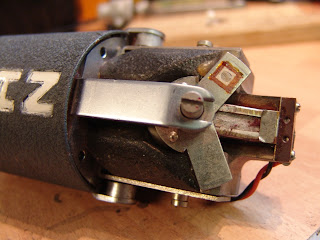

The M360 is slightly larger and like the M320 it also has an acoustic chamber below the ribbon motor. I was fully expecting to see the same motor in this mic as is found in the other Beyerdynamic ribbon microphones of the same era, so was suprised to find something quite different. Rather than being assembled from four small magnets glued together, the M260 has a larger cast magnet with two copper coloured pole pieces which may also be a magnetic alloy.

|

| Beyer M360 motor |

Although the motor is wider and deeper, it still accommodates the same size of ribbon. And the magnetic field measures around 5000 Gauss, which is similar to a ‘normal’ healthy Beyerdynamic motor. So I am really not sure why this uses a different motor. Perhaps it was an early production run. The transformer and switch (on/off) are housed below the acoustic chamber below the microphone.

In the photo above, the ribbon is fully corrugated, but another specimen (below) had a standard Beyer ribbon, which seems more likely to be the original.

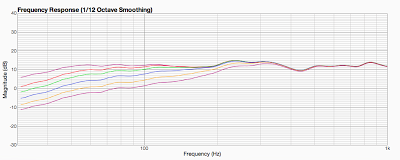

Both mics sound good when working properly, with a cardioid pickup, a relatively flat response and a bit less proximity effect than you would find in a figure-8 ribbon. They use the typical tiny Beyer transformers, which in the case of the M60 at least is wound for a full range response.

*Here is the full Beyerdynamic catalog from 1965, at the excellent Coutant website.

Huge heavy Meico dynamic mic

Here is another big old dynamic microphone, this time made by Meico.

|

| Meico Dynamic microphone |

The big ferrous magnet inside the mic bring the weight up to nearly 1.5 Kg!

|

| This one is certainly a heavyweight! |

The badge is very cool though, and the star and wings look like it might be inspired by Soviet artwork of the era!

|

| Like Mexico, but without the X…. |

According to this eBay seller, the mics were made in Congleton, and they were used as announcer’s mics in boxing matches. I have found nothing to confirm or deny this, so as always if you know more than I do, please get in touch!

But if it fell on your head, then it would certainly be…. a knockout.

(Sorry)

Oktava ML16 ribbon microphone dissected

MOTM – Toshiba Type K multi-pattern ribbon mic

|

| Toshiba Model K |

|

| Rear of the model K, with pattern control |

Inside the mic, the motor is based around a single strong horseshoe magnet, with the ribbon held between two chunky pole pieces.

Like the RCA 77DX, there is an acoustic labyrinth made from a series of holes with connecting channels, which goes up and down the centre of the mic. Two thick wires take the signal from the ribbon, through the labyrinth, down to the transformer below.

|

| Acoustic labyrinth in the middle of the mic |

The pattern control uses a choice of baffles to partly or entirely redirect the rear of the ribbon into the acoustic labyrinth. This turns the mic into a pressure transducer when the rear baffle is closed, giving a more omnidirection pattern.

|

| Pattern control on the Toshiba type G. |

It differs from the RCA design: the 77DX has a a cam shaped copper plate that allows the rear vent to be opened by incremental amounts, whereas the Toshiba has three discrete positions, which are labelled…

- N (fully closed – non-directional)

- B (fully open – bidirectional or figure 8), and

- U (a small opening – unidirectional or cardioid)

And in an attempt to beat the Americans, on the bottom of the mic there is a switch for a 6 position variable frequency high pass filter – the RCA77DX only has three!

|

| High pass filter switch |

The Bang and Olufsen ribbon microphone family

|

| B&O ribbon mics, from left, 2x BM2, 2x BM3, 2x BM6, 3x BM5 stereo |

As far as I can tell, the first commercially available B&O ribbon mic was the BM2 – which begs the question “what happened to the BM1?” There seems to a bit of confusion about this, and possibly there never was a model called BM1. According to Beophile, the first B&O microphone was a dynamic mic called MD1. However, others have listed this as BM1. Numbers 2 to 7 were ribbons and carried the prefix BM, which may have stood for ‘baand mikrofon’ – Danish for ribbon microphone. Although it could also have stood for beomic. The MD8 was also a dynamic.

|

| B&O BM2 ribbon microphone |

Regardless of the BM1 (or lack thereof), the BM2 is a good-looking microphone, with a very different look to the later mics. It has a cast metal body and folded, chromed brass grill. The mics were painted in a green-yellow textured paint, which looks better than that sounds! They are usually* 50Ω mics, with an a switch which connects an inductor into the circuit, for a high pass filter. The ribbon is held in a removable frame, which slides out for servicing. (*They can be re-wound for 300Ω, to great effect).

The BM3 and BM4 look very similar to one another, and used an evolution of the motor assembly in the BM2, this time in conjunction with a steel tube body. This design set the style for all their later ribbon mics, and also inspired Speiden and Royer microphones, and a bunch of clones such as this Stellar mic.

|

| B&O BM3 microphones |

In the case of the BM3, the ribbon motor frame is larger than the diameter of the tube and sticks out from the sides of the mic, giving it the look of a long face with ears, or perhaps Doctor Who’s Cybermen. It has a three way selector switch which provides M (music – full range), T (talk – HPF) and 0 (off) positions.

|

| Motor frame from the BM3, with Xaudia transformer, awaiting a new ribbon |

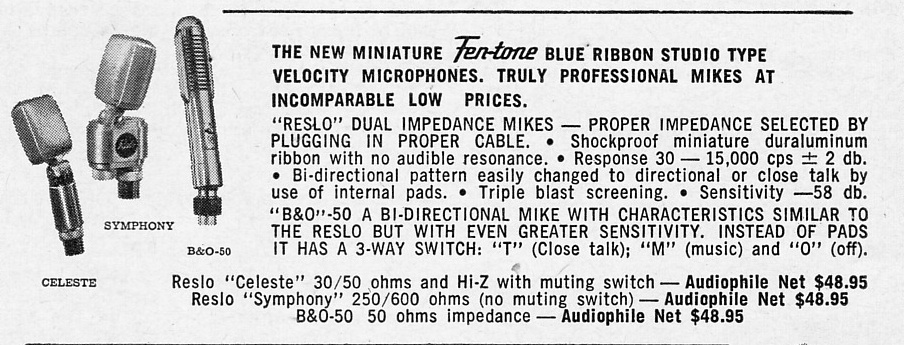

The BM4 looks the same as the the BM3, but with an additional switch at the rear for selecting 50, 250Ω, or high impedance output. The BM3s were fixed at 50Ω (and benefit from a matching transformer or upgrade). Occasionally you see these badged as “Fentone”, although, oddly enough, they kept the B&O name on the mic too.

|

| Fen-tone add showing the BM3 – from Preservation Sound |

The BM5, BM6 and BM7 came later and formed a family of mics. The BM5 is the stereo model, and when rotated to 90 degrees, it is perfect for Blumlein pair recordings. The bottom half of the BM5 was available separately as the mono BM6, and the top was called the BM7, although it could not be used by itself.

|

| Standard BM5 stereo set with stand |

The design was an evolution of the BM4, but by this point the ribbon frame and been replaced by plastic mounts, and the cyber-ears have gone. The magnets are also slimmed down, with a semicircular or triangular cut-out, presumably in an attempt to increase the high frequency response. In these mics the body of the mic is made from steel and also acts as the magnetic return path, which helps to increase the output.

|

| Insides of a B&O BM6 ribbon mic. Note the pistonic ribbon |

Like all of Bang and Olufsen ribbon mics, the BM5/6/7 family have a pistonic ribbon, which is gently curved in the middle and deeply corrugated at each end. The ribbons were made from Duralum alloy, which contains copper in addition to aluminium, to improve the strength and stiffness. However, the alloy is more prone to corrosion than pure aluminium, and it is quite rare to find ribbons that are in perfect condition.

|

| Delux BM5 set in posh wooden box! |

From a technician’s perspective, these later mics are less robust than the BM3/4. To me they feel more of a hi-fi design than one for a busy working studio. Although the sound is excellent, they are delicate in places and some of the plastic parts deteriorate with age, most noticeably the rotating ring in the top part of the mic. The switch tips also have a tendency to come off.

|

| Plug for a B&O BM3 microphone |

All the B&O mics used bespoke connectors, which can be hard to find. the BM2, 3 and 4 have a 3 pin connector only found on B&O equipment, whereas the BM5 and 6 used 5-pin DIN connectors but with their own threaded locking ring. The latter can be replaced with a standard bayonet DIN if the cable is missing.

Here are some links to wiring diagrams for some of the mics.

BM3 data sheet

BM4 data sheet

BM6 data sheet

BM7 data sheet

Thanks to Tom Day and Robin Kiszka-Kanowitz for additional information.

Update 1/2/18

Our friends at Extinct Audio now manufacture the BM9 studio ribbon microphone, which shows the influenced of the B&O designs.

Update 4/3/14

We now have upgrade magnets and transformers for all B&O microphones.

Update 22/4/13

Many thanks to Evan Lorden for sharing these photos of his B&O MD1.

Geloso M88 dynamic microphone

Here is a pair of funny little Geloso dynamic microphones, one is in pieces already.

|

| Geloso M88 dynamic mics |

The build quality is nice – better than the early Geloso mics which tend to crumble. It has an internal two-bobbin humbucking transformer, to give an output impedance of 250 ohms.

|

| Internal transformer for impedance matching duties |

The diaphragm is made from a light plastic for fast response, and they sound nice, if a little light on bass.

|

| Geloso M88 diaphragm in good shape |

|

| The original unobtanium connector can be converted to XLR |

🙂

Short, stubby and dynamic – The Reslo PGD

Reslos are best known for their ribbon mics, but they made some dynamics too.

|

| Short, stubby and dynamic – The Reslo PGD |

The PGD appears to be made of leftover parts from the RV ribbon mics. The base of the mic is the same, complete with swivel mechanism, and the grill looks like a cut down version of the RB too. As usual it uses the annoying Reslo plug.

|

| The head on the RGB could be tilted for best pickup of sound. |

|

| Reslo PGD – aluminium diaphragm |

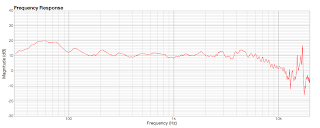

Like many early dynamics, it has a pressed aluminium diaphragm, which is heavy and stiff compared to later polymer film designs. Consequently has a quite lumpy response. Here is a frequency plot for one mic – other examples may differ!

|

| Frequency sweep for Reslo PGD mic. |

Experiments with Carbon Microphones

They were really simple devices, with small particles of carbon packed into a space between two electrodes and pressed against a plastic, mica, rubber, or wax paper diaphragm. When connected to a battery supply, a current flows through the mic which is modulated as the sound impinging on the diaphragm compresses and releases the carbon particles.

|

| Old carbon microphone – unknown manufacturer |

The body of the mic is made of an insulating material, in this case a block of marble. The classic Marconi-Reisz microphone also used marble – this one is clearly a copy of that mic. Others had bodies made of wood, which must have been cheaper to make. Four hooks screwed into the body would have been used to suspend the mic within a metal ring, using springs or rubber rings, like this nice example at the ORBEM website.

|

| Old diaphragm and grill from a carbon mic |

After many decades this example is in pretty poor shape: most of the carbon has escaped into the wild, and the diaphragm is cracked and perforated. I wanted to try and get this working again, for fun and as a learning experience.

|

| Clean again! |

The first step was to clean everything up in the ultrasonic bath, and the brass terminals were given a scrub. At least it looks better! The carbon will sit in the depression between the two brass terminals.

|

| New diaphragm ! |

I made a new diaphragm by stretching a sheet of thick cellophane over the bakelite frame that makes up the front of the mic, and then heated it gently with a hot air gun. The plastic film shrinks and pulls itself tight. It looks neat and has a similar thickness to the original – as far as I can tell.

Then the mic can be re-assembled and filled with new carbon granules. It takes a few goes to pack the carbon, shaking the mic in between each fill.

|

| Carbon microphone circuit, from the TFPro website. |

I tried a circuit inspired by the one above, using a battery and transformer. Ideally the transformer should be gapped, or a capacitor used to block the DC, to prevent saturation.

With a new diaphragm and new carbon, the microphone does now pick up sound, and although it is far to noisy for any serious recording, I was pleased just to get that far in my first attempt. As always with microphones, the art is in the detail and I can now at least appreciate some of the design parameters than need to be considered. These include

- Diaphragm material, tension, thickness and stiffness. The diaphragm needs to be thin and compliant enough to vibrate, yet stiff enough to transfer the energy to the carbon granules. Cellophane may perhaps be too flexible, but glass or hard plastic could be too stiff.

- Carbon granule type, size and packing. The carbon needs to be compress reversibly by the diaphragm, otherwise it will pack and stop working.

- Impedance. I noticed that the impedance of the mic dropped from about 10K ohms to 1K ohms on tightening the filling screw. Clearly some pressure on the granules makes a big difference to the impedance, and also made an audible difference to the sound of the mic.

- Terminal size and shape. The contact with the carbon granules will affect the impedance of the mic and the efficiency.

- Circuit. Varying the voltage across the mic made a noticeable difference to the noise level. The transformer should be capable of taking some DC current, or a capacitor used to block the DC. (which is how I did it)

There is also a nice blog post about carbon mics at Preservation Sound.

MOTM: Siemens-Telefunken M201/1 Ribbon

We have seen an influx of weird and wonderful ribbon microphones this month, including a rash of Bang and Olufsens, half a dozen Film Industries mics, and a cardioid Toshiba BK5 copy, so we were spoilt for choice for a Microphone of the Month…. until this came along…

|

| Telefunken M201/1 cardioid ribbon microphone |

The Telefunken M201/1 was one of the very first commercial ribbon microphones. It was made by around the early 1930s and would most likely have been used for radio broadcast. These ribbon mics were a big improvement on the carbon microphones that they replaced, but in Germany they were quickly superseded by the new valve condenser microphone technology.

|

| Telefunken logo on the M201/1 microphone |

There are very few of these left in circulation – this one is in very nice condition and after a clean and a new ribbon sounds truly excellent, with a strong output not much below a modern dynamic.* After over 80 years, the magnets are still strong with a field on >5000 Gauss in the narrow 2.5 mm gap between the ribbons.

|

| Telefunken M201/1 rear |

The M201/1 is constructed around a huge horseshoe magnet, which surrounds the transformer and (presumably) some kind of acoustic labyrinth or wadding to control the pattern. This dictates the shape of the body and gives it an unusual cylindrical aspect. The ribbon sits behind a fine brass grill at the front of the mic. With the rear of the ribbon being obstructed by the magnet, the mic is almost cardioid in nature, becoming more figure of 8 towards the very bottom of the frequency range. Two chrome B-shaped vents sit above and below the ribbon to equalise the pressure behind the ribbon. The output connection is made via a pair of screw terminals hidden behind a circular plate on the rear of the mic.

|

| M201 ribbon |

The ribbon itself is long and thin, and the old broken one inside the mic was fully corrugated (the one shown is a replacement). For ‘ease of service’ the ribbon is held in a frame behind the front grill. However, once in place the assembly hides the ribbon pole pieces from sight, which means that alignment is a case of trial and error, which is possibly the only weak part of the design that I have found. With the new ribbon, the mic has an output impedance of around 300 ohms.

|

| Telefunken M201 under test |

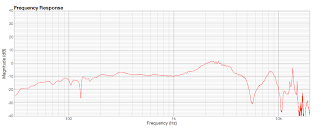

I did a test sweep of the mic in our little testing chamber.** The mic shows a strong output with good bass response, a little proximity effect below 100Hz, and a graceful roll-off above 6KHz. The noise above 14KHz are likely to be diffraction from the grill and other parts.

This microphone is thought to have been made originally by Siemens & Halske and supplied under various model numbers including the KVM3, SM3 and others, and this rather wonderful example on Martin Mitchell’s excellent microphone blog, which is just called model ‘R’. In German a ribbon mic is called a Bändchen-mikrofon. However, the name plate on this is in English, and perhaps this is the export model, with the R simply for Ribbon. There is a bit more history at Martin’s blog, which is well worth a read.

|

| Mitchell’s Siemens type R ribbon microphone |

* Testing against a Shure Beta57, the preamps were on the same gain setting for a comparable output

**Calibration is with an omni measurement mic, so there can be some bumps due to the differences in pattern picking up more or less reflections from the room.