The Bruno Velotron (made by and sometimes badged as Webster) was an oddball microphone that took inspiration from both ribbon and condenser technology. Strips of aluminium foil were attached to an insulated metal backplate, and a voltage applied between the two. As the foil vibrates, the capacitance of the device varies, and a signal is generated. They are notoriously fragile, and there are very few around in working condition.

|

| Bruno Velotron microphone |

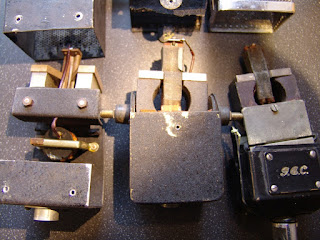

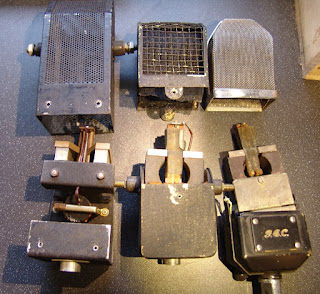

I found this one on ebay a few months ago and could not resist grabbing it for dissection and possible resurrection. The specimen is in very good cosmetic condition so will look nice in the collection even if it it is beyond repair. But it would be even nicer if we could hear it in action!

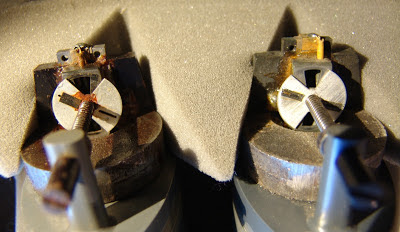

Looking inside, the element is marked ‘4½M’ and 2/4/38, which in American would be 4th Feb 1938. The ‘4½M’ may refer to the impedance of the device.

|

| Velotron element |

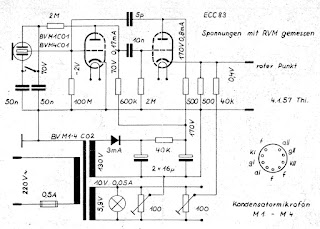

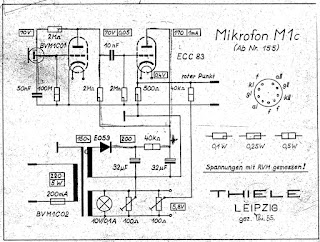

The Velotron requires a polarisation supply and a buffer amplifier to operate – I am not sure if these came with the mic, but the tube amps of the era could easily have been modified to provide this from the high voltage supply. The excellent Coutant.org shows a wiring diagram for a suitable polarisation supply and buffer amplifier…

|

| Supply for Bruno microphone – from Coutant.org |

Based on this diagram, I wired a 7205 subminiature tube into one of our tube microphone power supplies, to act as a little amplifier circuit for the mic.

|

| Hacking together a power supply and amplifier. |

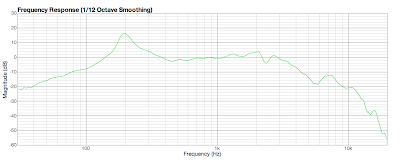

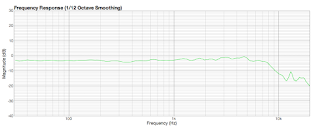

Miraculously, the microphone worked on the first attempt, even after 74 years! The sound is very warm and dark with an obvious roll off at the top end, and it was very exciting to hear one of these for the first time.

|

| Bruno Velotron – frequency plot |

I wondered if some of the roll-off may be due to cable capacitance – if the element really does have an impedance of the order of 4.5 MΩ then even a few tens of pF will become significant. However, swapping cables and using a triaxial arrangement didn’t make any different, so it may well just be the natural response of the beast, and certainly how it would have sounded at the time.

The mic is unfortunately prone to noise and pops. They are notorious for breakdown of the insulation on the backplate and that seems to be the case with this one. So the next job would be to drill out the rivets that hold the element together, strip off the ‘ribbon’ foil and re-lacquer the back plate.

Update 27/5/13: It seems that these were sold in Europe under the Radio Marelli brand. As seen on ebay….